In this article I will introduce you to the command line, or bash equivalent ones at least. These are the command lines you find in operating systems such as GNU/Linux, Mac OS X, BSD-family, and more. On Windows, you can use the Linux Subsystem, Cygwin, Git Bash or something else as well. There are many options here! On some systems these applications can be found as Terminal, Terminal Emulator, Command Line, or something similar. This guide is structured with different headings, each covering different topics related to the command line. In the info-boxes, you will find extra information that might help you with terminology or other things that will help you. Most of this information is optional, so don't be scared if there is something you don't completely understand the first time you read it. Let's get started on your journey to learn the command line!

Prerequisites

The only thing you need to follow this guide is to have a terminal/command line on your system, which is in the Bash-family of command lines. That's it! This does NOT include Windows CMD or Powershell, as these are different beasts (CMD have more in common with MS DOS than Bash-based command lines). All standard terminals for Linux distributions and Mac OS X will work, as well as the previously defined options for Windows (Linux Subsystem, Cygwin, Git Bash).

It might also be a good idea to have a text editor handy, to create text files we can play with (and later scripting if you find that interesting!). One option here on Linux-distros are programs like GEdit, or TextEdit on Mac OS (with plain text chosen as the type of file). Other editors include Vim, Emacs, Visual Studio Code, Atom or something else you might enjoy using (or want to learn). I personally use Emacs for almost everything (including writing this guide), but understand that it might be a little daunting for beginners.

Why should you learn to use the command line in 2021 (or later)?

There are many reasons to learn the command line! Some of them include:

- Operation of servers. may do not have graphical user interfaces. Logging into these using a command line (with for example SSH)

- Docker, Kubernetes or other cloud native methods of operating modern infrastructure. Developers are expected to know more about operations these days, and being good in the command line is often necessary to debug issues with applications running on these "platforms".

- Automate repetitive tasks. Either using standard scripts, using Ansible in combination with scripts and more!

- You are a programmer who want to to be able to use tooling that might not exist in your IDE (but has a command line interface). While you can configure the run of many different programs directly in your IDE, it can sometimes be tedious. There are IDEs with command lines built in as well, so a combination of IDE and learning the command line can make you more productive.

- For fun! Maybe you love computers, but haven't really done much with the command line yet. You will beyond any reasonable doubt be more productive (or faster)! It might also make you more comfortable using a computer without distractions for doing even the simplest things (like file management). The last part holds true for me, as I find most graphical file managers to be nauseating.

Your first command!

So you have finally come this far? You are ready to type in your first commands and experience the wonders of the command line for the first(ish) time? Let's start by opening your command line application / terminal emulator, then typing pwd, which might look something like this (including your prompt):

/Users/marie $ pwd /Users/marie

This prints the directory you are currently in. You may often see this path printed before your prompt (which is here denoted by a dollar sign). On my Mac we see that we are in my home directory. If you are on a GNU/Linux system this would have looked like /home/marie. The home-folder is also denoted with the tilde symbol, ~ in most command lines.

I will assume that you either are in your home folder or another folder where you are allowed to view and edit files for the remainder of this guide.

Now we have opened our terminal and typed our first command, let's continue to more exciting commands!

If you decide to play with something like Docker, then you will see # in your shells unless you specify another user for the container (explaining containers is beyond the scope of this article. Think fo it as a light-weight virtual machine for now, even if it is an oversimplification).

You might have heard the concept of sudo? sudo is a way to run programs as root/admin, even if you are not yourself the root-user. We will not go further into that concept in this guide, but now you at least know what it means.

File management and navigation

pwd was probably a very uninteresting command to start with, but don't worry! Now we begin with some real commands for navigation and looking at your files, before continuing with even more interesting commands as each section progresses!

ls - list directory

We are currently in a directory, but how do we see the files in it? This is where the ls comes in! You might see something like this:

~ $ ls Documents Downloads Pictures myfile.txt

These are the sub-directories in your current directory. You might also want to see hidden files:

~ $ ls -a . .. .local .Trash Documents Downlads Pictures myfile.txt

Hidden files usually start with a dot in their name, and these files are usually settings (text files) for programs you may use (Docker, Emacs etc.). You may also notice the . and .. above, which have special meanings in command lines. These denote the current directory (.), and the parent directory (..) respectively. (parent directory as in "one directory up")

-rw-r--r-- 1 marie staff 984 Jul 1 17:16 myfile.txt

What does this data mean? You might deduce the 984 number to mean file size, the other info for when the file was created or change, as well as who did it. What does this -rw-r--r-- mean? The first dash denotes if it is a directory or not. If it's a directory, that dash would have been a d. The rest is the permissions for your user, group and all other. r means read, w means write and x means execute (run as a program). The r,w and x will always be in the same places, so don't worry about them sliding around!

How would we go about changing it? For that we can use the chmod (change modifier) command. One example is chmod 777 myfile.txt (all permissions for all), chmod +r myfile.txt (give ourselves read permissions) and so on. As you can see pretty simple!

If you are very curious about something at this point, it is probably what the 777 means in the chmod example above. These are octal numbers! That means a number system with 0-7, where 8 denotes the same place as 10 does in our decimal/base 10 number system we usually use. What is so great about octals, and why does it make sense for the chmod file permissions? Notice (if you are familiar with binary numbers, 0 and 1), that we only need 3 bits to cover 0-7 (000 is 0, 001 is 1, ... up to 111 which is 7). If you are perceptive, you will have noticed that each of the bits can be a flag for a permission! Where 111 (or 7) means all permissions on!

cd - change directory

For now, we have been stuck at our starting directory. Let's change that! If we are still in our home folders, we can navigate to our Documents folder (or another folder if your folder structure is different):

~ $ cd Documents ~/Documents/ $

As you can see, we are now in the documents folder! If you want to navigate back to your home-folder, you can use the .. name:

~/Documents/ $ cd .. ~ $

As you can see, we have now navigated back. You don't even need to navigate one directory at a time, you can use deeper directories, the special symbols (. and ..). Example (your machine will be different as you probably have a different set of files):

~ $ cd Documents/Budgets/2019

rm - remove/delete file

Want to delete a file? The rm command is at your service! Just do rm myfile.txt and myfile.txt will be removed/deleted. You can use complete paths (like Documents/Budgets/2019/myfile.txt) as well as files in the same folder here. If you want to delete multiple files, you can add them after your first. rm myfirstfile.txt myotherfile.txt yetanother.txt (or more files if you want to)

rmdir - remove/delete (empty) directory

Let's say you want to delete a directory with no files in it? There is a command for that as well! rmdir Documents will delete your Documents directory if it's empty. (see the previous info-box on rm -rf for deleting non-empty directories and some dangers for beginners relating to this command).

mkdir - create a directory

Just like rmdir deletes an empty directory, mkdir creates one! mkdir Documents will create a directory called documents.

cp - copy file

Want to copy a file to another destination? The command is simple; cp followed by the full path of the file you want to copy (either a filename or a path like Documents/Budgets/2019/mybudget.txt) and the destination (either just a filename or a complete new path). Example:

~ $ cp myfile.txt mycopy.txt

Now you will have a copy of myfile called mycopy. You can even change the filetype if you want! (no conversion happens, just the name of its ending which denotes the type of file). Copying a directory is simple, you just add the -R option:

~ $ cp -R Documents Documents_copy

Or maybe you have gotten a tar file? tar -xf mytar.tar

Or maybe a tar.gz file? tar -zxf mytar.tar.gz (tar.gz is something called a gzipped tar, or compressed if you will).

Later I will recommend you places to find information on the options of these commands. Then your exercise can be how to use the tar program to create your own tar archives!

Viewing files in your terminal/command line

So far we have navigated around, deleted files, copied and so on, but we have never really viewed our file contents outside a text editor. In this section we will do exactly that!

cat

The simplest way to view a file is the cat command. cat simply prints the content of the file like this:

~ $ cat myfile.txt This is some text in my file ~ $

(the last line is mean to symbolize that we just return back to the command line after the contents have been printed)

less

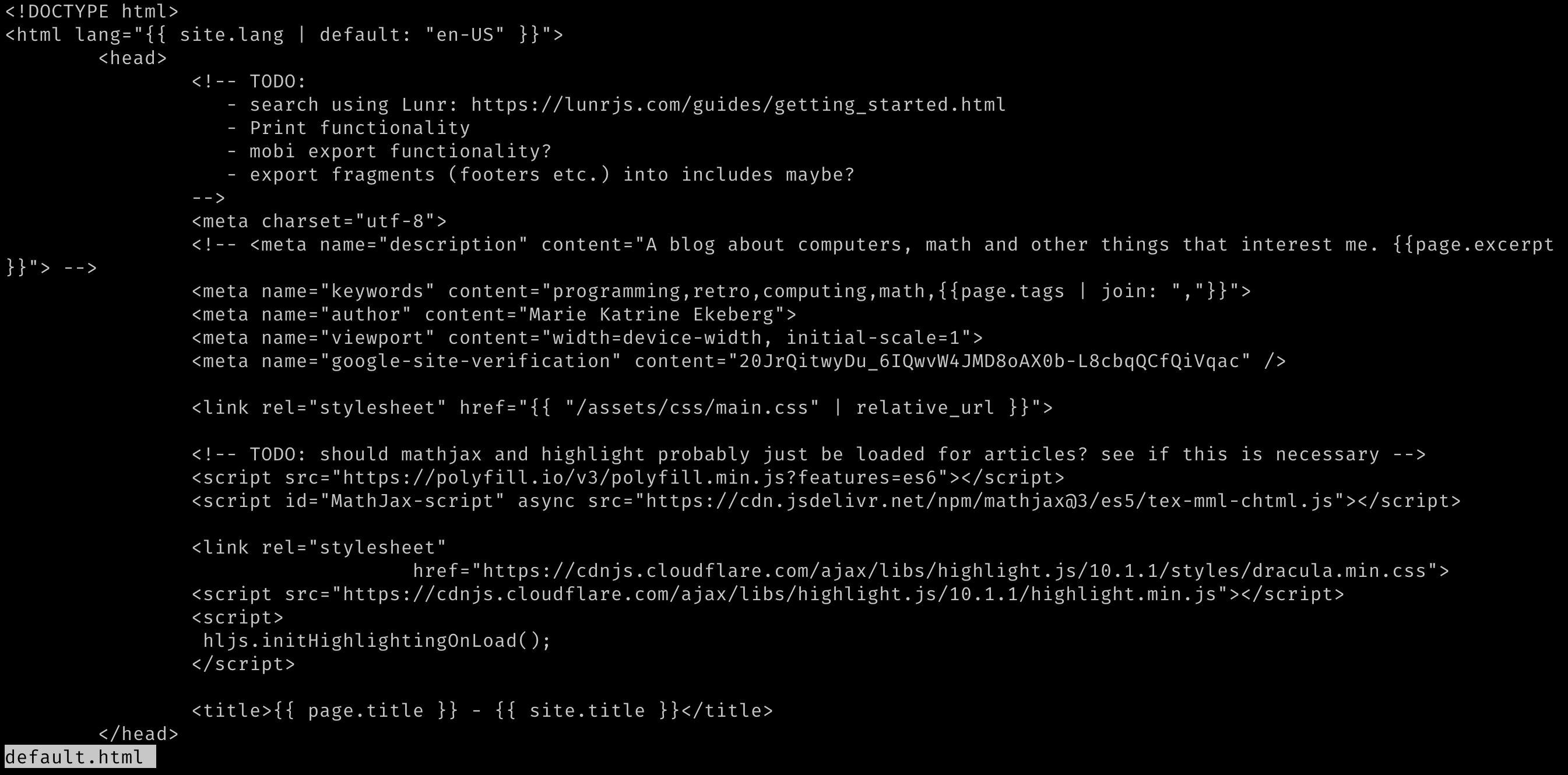

A slightly more advanced way of viewing files is to use the command called less. less let's us navigate our file and view it as well. For one of my files (my default layout for this blog) it looks like this:

Some people may wonder how to navigate in less, and how to exit? You can exit with q and navigate with the error keys. That is the most important things to know. You can also navigate with PageUp/PageDown if you want to, or the hjkl-keys (h = left, j = up, k = down and l = right).

To search the contents of a file you can use the / command, and then write your search term followed by the Enter-key. The n key will navigate to our next match, while the N key finds our previous match (if we have navigated forward, but want to go back).

Piping

Let us quickly introduce echo to make our examples more clear. echo simply prints its input:

~ $ echo "Hi, this text is printed" Hi, this text is printed

Before we continue on to our next section, it might be useful to learn what piping is. This concept can seem a bit daunting when you first start using the command line, but trust me: it is not that complicated! There are two main ways of piping that you should know of:

|Standard pipe. Sends the output of the first program (left side) to the second (right side). We will see an example of this in the next session.>File pipe. Sends the output of the first program (left side) to the file with the name of the right side. If the file already exist, it is overwritten.echo "Hi I am the beginning of a file" > myfile.txtmakes a new file (or overwrites existing file) with the text from the echo command in it.>>Concatenation pipe. Sends the output of the first program (left side) to the file with the name of the right side, but concatenates the output to the end of the file instead of overwriting it.echo "Hi i am the next line" >> myfile.txtadds the text output from echo to the end of the selected files (aka appends it to the end of the file).

All of the above can be used with almost any program! Feel free to mix and match! Maybe you want to create a report from an earlier program run and add it to a file? Or search a big text with cat and grep? (see next section). There are many possibilities here, and knowing about pipes can be pretty useful to be more effective in the command line!

Searching

Sometimes you may not know where a file is, or may want to know which line of a file a given text resides.

find - finding files matching criteria

find can be used for many things, including finding files matching a given name. This is the most common use-case and what we will cover the basics of here. If you are curious about more ways to use find, you can find documentation using the resources in the next section (Finding documentation).

Let say we want to search for a file containing the term books in its name, then we can use the command find . -name '*books*'. This finds all the files with books in its name. The stars are wildcards, so if you removed the first star it would search for all files starting with the name books. (I guess you can guess what happens if we remove the last star?)

grep - search content in files and input text

Let's say we want to search for contents in files instead. The simplest use case can be covered with the command grep -Rn "My Search Text" . (. for search to begin in the same directory we are in). Then you will get each occurrence listed. Each line will look like this (here I have searched for Clive Sinclair on the local files for this blog):

./themkat.github.io/_posts/2021-09-18-rip_clive_sinclair.html:3:title: Sir Clive Sinclair (1940-2021)

So as you can see, the file, line number and matching text is printed. the options R above means recursive (search sub-directories as well), and n means show line numbers.

What if we instead wanted to supply grep with a text and search that text ourselves? Maybe also using the pipe | above? Let us do exactly that: cat myfile.txt | grep "My Search text" would search our text for My Search Text. You can swap the cat part with almost any command you would want. This is where I use grep most, do search in output of other programs. Programmers may recognize this usage with logs from programs, compilations, test runs or something else.

Finding documentation

So far some of the options to the programs above may seem a little bit cryptic. How do people learn about all of them? Well, you rarely need to know all of them, but there are resources to make them easier to handle.

The most Unix-y way is a concept called man (as in manual) pages. man pages shows you documentations to many things in a Unix-based system, including the commands above! (also C header files if you want to learn C programming down the road!). man is very easy to use, just type man, followed by the command you want documentation on, and you will see the documentation directly in your command line! Navigation is done the same way as less! To get you started, maybe you can view the man-pages (and maybe also expand your understanding and usage!) of some of the programs above, as well as some new ones:

- tar (seen in an info-box above)

- find

- grep

- chmod

- date

- kill

- curl

NB! man-pages may not be available on Windows unless you specifically install them! On Mac OS X and Linux-based systems they will be there by default for most of the programs in this article.

If you have issues viewing man-pages, you can do so online on a page like man7. For example for the less command.

If you have problems, there is always Google, DuckDuckGo or another search engine there to help you. StackOverflow also have many answers to questions about command line tools.

A whirlwind tour of scripting

Covering everything about shell scripting would make this guide way to long, as the topic is worthy of an article in itself. (let me know if you would want one!). There are several good resources to get you started, like ShellScript.sh or the man-page for bash (man bash).

Scripting is probably the most interesting part for you if automation was what got you started on your command line journey. To simplify a bit: scripts are just a file we run with commands that we want done. Let us now create our first script. Open your text editor and create a file like this:

#!/bin/bash echo "Hi $1"

Then save it as hello.sh (or another name with the sh ending). Use chmod to make it executable/runnable (chmod +x hello.sh), run it:

~ $ ./hello.sh Marie Hi Marie

As you can see, it printed my name. The dollar sign denotes the argument to the program (in this case my name). You can have multiple or no arguments depending on your problem, and they will be enumerated based upon their position ($1 is the first, $2 the second and so on). The stuff at the top of the file is simply called a shebang, which denotes how the program should be run. If you ever use other scripting languages than bash (yes, there are more!) like Python or Perl, this part will look different.

This is all very simple, but you can mix and match any of the programs we have used above! Maybe you want conditional run based upon the input the program?

#!/bin/bash

if [[ $1 == "Unix" ]]; then

echo "Unix is love, unix is life";

else

echo "Hi $1"

fi

This quickly introduces the if-expression where we can test for various conditions (here for a matching text). This is only the beginning of what you can do with shell scripting! So why not try to use some of the commands above and automate something? Or maybe if you are interested, read some of the resources I mentioned at the beginning? Or if you prefer, bug me to create a bash shell scripting article…

What's next?

Now you have gotten started and learned the basics of the command line, and even some shell scripting. What's next? Depending on your skill level and what you want to achieve, there are several options ahead! I can not possibly make an exhaustive list of everything you want to do, but below are some suggestions:

- Learning how to use scripting to configure your terminal with a .bashrc file (or .zshrc if you use ZShell which is now the default on Mac OS X).

- Learn a command line text editor like Vim or Emacs

- More useful programs for scripts like dialog. Or even more useful, text management programs like sed and awk (worthy of their own articles!). There are also several articles on various command line tools on this blog (#1 and #2).

- Learn how to use the ssh command to log into servers you may have access to (maybe you have an Amazon EC2 instance running? Or maybe your workplace or University have a server you can log into?)

- Automating more with a program like Ansible

- Learning about containers and Docker, which is a prerequisite for learning something like Kubernetes. If you want to go down this path, KataCoda has interactive exercises right in the browser!

- A more fancy command line with auto completions, more options for scripting and even more goodies? Try something like ZShell (default on Mac OS X) with Oh-My-Zsh installed. This gives a more modern command line that I can wholeheartedly recommend! :)

Want a guide like this going more in depth on the tools below? Or maybe some of the next steps mentioned here? Say so in the comments, and it might happen!

Is anything above unclear? Feel free to ask questions in the comments and I will answer when I can! :)